A disclaimer: I’m still learning. Some of this information about when people use usted or tú might not be perfectly, precisely accurate. And a lot of it won’t apply broadly. My grasp of this topic is based on my observations and the conversations I’ve had with people in a few different Spanish-speaking countries. However, there is so much variation–even within a single country. I’m convinced someone could write a master’s thesis on this.

Usted or Tú, The Basics

You might already know that there are two words in Spanish that mean “you”: tú (“too”) and usted (ooh-STED). (There are a few others. But they’re rare enough in my day-to-day life to not be relevant here.) When I started practicing with Duolingo, they gave me a simplistic explanation about when to use usted or tú. Tú is the more informal way to address someone, and usted is more formal. However, with time and exposure, I’ve found that there is a lot more subtlety and cultural variation than I realized. As it turns out, I decided to move to a place where this topic is particularly convoluted.

A Brief Grammatical Explanation

Why is it so difficult? Let’s start with the grammar.

Besides having two different words for “you”, there are entirely different verb conjugations, depending on which “you” you’re using. For example, in English, you can say, “You write,” to anyone and everyone. But in Spanish you would say either, “Usted escribe,” or, “Tú escribes,” depending on who you’re talking to.

This means that when I’m speaking Spanish, I need to constantly be conscious of whether I’m addressing someone as usted or tú, and conjugate my verbs accordingly.

Usteo, Tuteo

There’s even a verb that means “to use the word tú and all of its accompanying verb conjugations”: tutear (“TOO-tay-are”). And its partner for the word usted: ustear (“OOH-stay-are”). To illustrate the complexity of Spanish conjugation, here’s a conjugation table for the verbs ustear and tutear. For the sake of simplicity, I’m not using their proper Spanish conjugations within the English sentences in this blog post.

| Who? | ustear (to use the word usted) | tutear (to use the word tú) |

| Yo (I) | usteo | tuteo |

| Tú (You) | usteas | tuteas |

| Usted (You) | ustea | tutea |

| Él, Ella (He, She) | ustea | tutea |

| Nosotros, Nosotras (We) | usteamos | tuteamos |

| Ellos, Ellas (They) | ustean | tutean |

You might have noticed that the conjugation for usted is the same as the conjugation for él and ella. This is what you use to talk about someone in the third person. To use my previous example, “You write,” is, “Usted escribe,” using the same verb conjugation as, “He writes,” or, “Él escribe.” It’s kind of like how a server at a fancy restaurant might say, “Would the gentleman like a beverage?” They’re addressing the gentleman, but in the third person.

A Japanese Parallel

Spanish isn’t the only language that uses different verb conjugations depending on the person with whom you’re speaking. In Japanese, there are also different verb forms to use depending on how formal you want to be. “You write,” could be “Anata wa kakimasu,” which is more formal, or “Anata wa kaku,” which is the direct form. In Japanese, this can be even more complicated. You can also add modifiers to any verb to emphasize your humility and/or your respect for the person you’re speaking to. Using “anata” can also be perceived as intimate, though Japanese doesn’t have another word for “you”.

Markers of Hierarchy and Distance

I studied Japanese in high school and college. I learned which circumstances called for the polite verb forms and which situations allowed for more direct speech. In general, you can use the direct form when you’re speaking with children, your friends and family, or someone who could be considered “beneath” you, like a student in the grade below you in high school, a lower-ranking employee at your job, or a pet. Conversely, you should use the polite or super-polite grammatical forms when speaking with strangers, clients, your boss, teachers, etc.

Honestly, this emphasis on status and hierarchy is one of the things that turns me off about Japanese culture. As an American accustomed to a more egalitarian style of speech, I found it frustrating to have to learn so many different ways to convey the same information with differing degrees of politeness. Fast forward ten years, and I found myself learning to be polite in a whole new language. I initially figured that the rules about when to use usted or tú would be pretty similar to the rules about using the polite and direct forms in Japanese. It was a decent proxy to start with, but it’s not perfect. As I learned more Spanish, I found more exceptions.

Where to Tutear With Everyone

The first stop on my year-long trip through Latin America was Guatemala, where I spent a month attending Spanish language schools. I learned that in Guatemala, it’s pretty common to tutear with just about everybody. Strangers, elders, teachers–you’re probably not going to offend or catch any flack for calling somebody tú. As you can probably guess, I liked the simplicity of this. Less fuss, less confusion, less hierarchy embedded in their speech.

But when I left Guatemala, and was traveling in other countries, I realized that I might have gotten a little too comfortable addressing people as tú. On a couple of occasions, I noticed a weird look or a pause in conversation, and I realized that it probably wasn’t appropriate to tutear with that person. Fortunately, it’s pretty obvious to everyone that I’m still learning, and I think people are generally a bit more forgiving with gringos (yes, in Latin America, I’m a gringa).

They might not be as forgiving with a native speaker. I have a BaseLang Spanish teacher who is from a region of Venezuela where it’s also common to tutear with everybody. She now lives in Medellín, Colombia, and told me about an occasion when a Colombian man got angry at her for presuming to tutear with him because he perceived it as a slight. He wasn’t aware that there is a lot of cultural context that determines whether someone says usted or tú.

People Who Ustear Exclusively

There are also places where it’s very rare to tutear. When I was in Costa Rica, I spent a lot of time with a family in Grecia who ustear exclusively. They call everyone usted: their family, their friends, kids, their partners, everyone. One of the brothers told me that in that part of the country, a lot of people don’t even know how to tutear–that is, they don’t know those verb conjugations because nobody uses them. I found that super interesting. For them, to ustear isn’t to emphasize anything about closeness or status. It’s just the way everyone speaks. And I appreciated the simplicity of that, too.

I have another Venezuelan Spanish teacher who is from a region of Venezuela where people ustear exclusively. He told me that this is more common in rural areas, where the farmers or campesinos have historically spoken more formally. He now lives in Lima, Peru, where people tell him not to call them usted because it makes them feel old.

It’s More Complicated in Colombia

Besides my broad curiosity about linguistics and my desire to learn to speak Spanish well, I’m usually doing my best to be polite. So, I’m working hard to figure out the subtleties of when to ustear and when to tutear now that I’ve moved to Colombia. I mostly do this by observing and listening to other people’s conversations and sometimes asking lots of questions. I’ve developed a general understanding, but Colombian rules and expectations around when and with whom to use usted or tú seem particularly convoluted. I’m going to outline the patterns I’ve noticed, but I’ll admit that a lot of what follows is hearsay and conjecture.

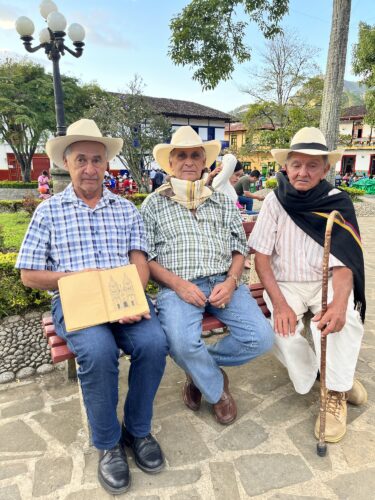

The area where I live has a big influence on my understanding. Most of the Colombians who I’ve spent a lot of time with are Paisas (from the departments of Antioquia, Caldas, Quindío, and Risaralda). There is a lot of rural farmland, mostly coffee production and cattle, and it’s been this way for a couple hundred years. As a result, lots of people around here are the children and grandchildren of campesinos.

Based on what my Venezuelan teacher told me, it makes sense that Paisas ustear more frequently. But unlike my Costa Rican friends, Paisas use a mix of tú and usted, often in ways that have surprised me. My impression is that some of the rules they follow for when to say usted or tú are specific to this region.

Gender Matters – Men Ustear More

It seems that in Colombia, when deciding whether to ustear or tutear, the gender of both the speaker and the listener matter. Sometimes it matters even more than factors like closeness and status. One of the things I’ve found surprising is that, at least around here, most men usually call other men usted. For example, my boyfriend will always ustear with his male best friend, male cousins, male strangers, male children, male dogs, etc.

For a month in early 2023, I was living with a Colombian family in a rural area in the eastern plains region (i.e. not Paisas). I was asking them about why men ustear more, and the dad told me that men tend to ustear with each other because to use tú implies a certain level of intimacy and familiarity. You tutear with your romantic partner. So if a man were to tutear with another man, he might be perceived as gay. (While Colombia is actually a pretty progressive place that mostly feels safe and welcoming for LGBTQ people, there’s obviously still some prejudice under there.)

However, I know a few Colombian men (not gay) who tutear with their male friends and family, and a few men (yes gay) who ustear a lot of the time. So, obviously, being gay has nothing to do with it, and there’s variability between speakers.

Men Who Tutear with Women

On the other hand, I’ve noticed that men often tutear with women. Not always. In business situations or service jobs, they tend to ustear. But I’ve noticed younger men sometimes using tú with older women in informal settings, even if they’re strangers. That is a case where I would probably err on the side of using usted. The prohibition on seeming overly familiar doesn’t always seem to apply, and I’m not sure why.

I don’t think there’s typically any sexist or disrespectful intent on the part of these men. They’re not calling men usted and women tú in order to consciously reinforce a gendered hierarchy. However, the fact that speech in this area has evolved in such a gendered way does make me wonder about its origins and history.

Taking My Cues from Other Women

Colombian women seem to tutear more, and age seems to matter more. Younger women seem to call most people tú, no matter their gender. It’s as though they’re a bit freer from the societal expectation of formality. Older women seem to use more of a mix.

I am more careful with people who are significantly older than me, and older members of my boyfriend’s family. In these cases, I just continue to ustear even if they tutear with me. Mostly because I feel like this is safe. Better to seem overly formal than overly familiar, I figure.

I don’t have that many female friends yet, but I’m paying a lot of attention to the way women speak because I need to take my cues from them. I’m trying to figure out what’s expected of me. My tactic is usually to wait and see whether someone is going to address me as usted or tú, and just match it. This mostly works well, except that I’ve had women of various ages use a mixture with me–sometimes calling me tú and sometimes usted, all within the same conversation.

So I have no idea what to do with that. It basically voids my working theory based on my knowledge of Japanese. There are different rules in play here, and I am still not clear on where the line is.

Calling Family Members Usted

The thing that most throws me for a loop is that many Paisas ustear with their families. But not exclusively, like my friends in Costa Rica. Here in Colombia, I’ve heard a lot of people ustear with their siblings, children, parents, and even pets. But I’ve noticed that people also tutear with these same members of their immediate family.

How do they decide whether to use usted or tú? It seems to loosely follow the basic patterns I’ve outlined above. Brothers will ustear more with their brothers than with their sisters. Women and younger people tutear more, but they do so less frequently with older family members. I’ve heard my boyfriend’s mom ustear with her sister and their father sometimes, but not always. I don’t yet know enough families to know definitively whether this is more common with older generations, but that’s my guess.

I think I’m confused because I’m still hung up on my simple, earlier understanding of this topic: I.e. call people you’re close with tú, and use usted for people you don’t know as well, or to whom you want to show particular respect. So when people call their siblings usted, it sounds to me like they are being super formal within their families. But their demeanor while they’re doing it doesn’t feel that way. So maybe there’s some kind of inversion happening here. Because these same people will sometimes tutear with strangers. Maybe to ustear with one’s family could also be a form of endearment?

What do You Think? Usted or Tú?

To be honest, I have more questions now than when I first started learning about this. I’ll continue to observe and ask questions, and maybe one day I’ll have an innate understanding of whether I should call someone usted or tú in Colombia. If you have any thoughts, I’d like to hear them.