My Evolving Awareness of Race

My awareness and perception of my racial identity has fluctuated, shifted, and evolved throughout my life. I think this is mostly due to having lived in a few different places with very different racial and ethnic demographics. Places where I was or was not unusual. Where I did or could not blend in. I learned about myself and the world from where and how I felt at ease, and where and how I did not.

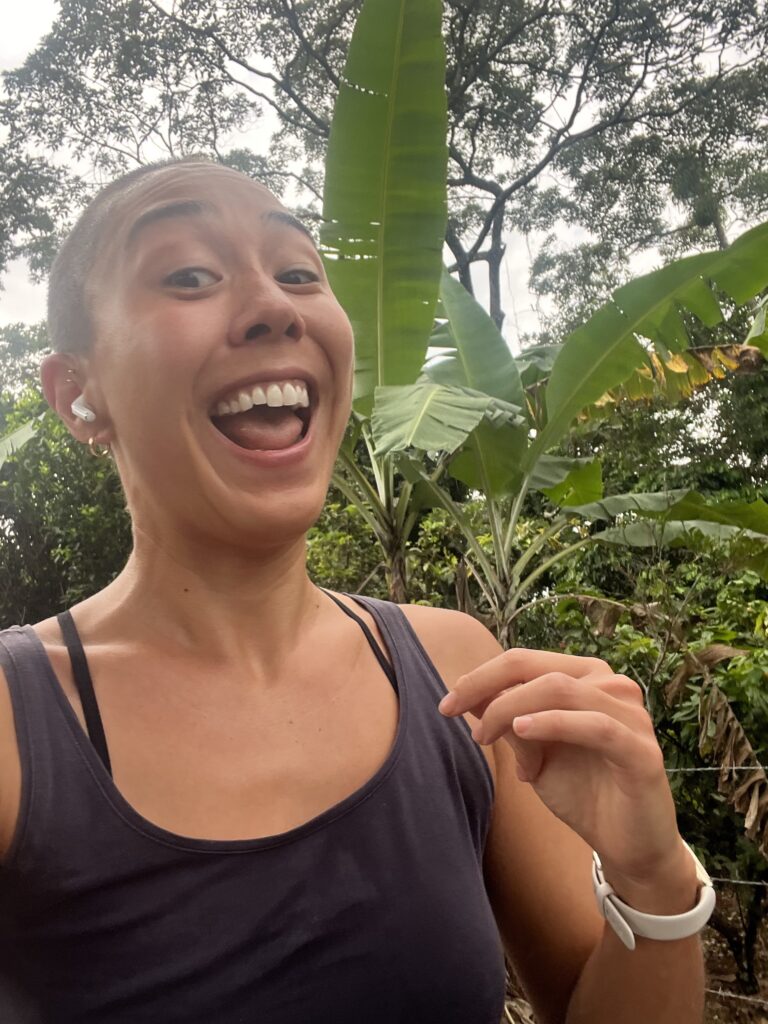

As I’ve traveled through Latin America, I’ve had a lot of opportunities to reflect on this theme. Particularly in the last five months, while I’ve been traveling in Colombia. It’s often occurred to me that I was the only Asian person in whichever town I was in. Which isn’t a completely alien experience for me, but it’s admittedly still a little weird.

Olo Olo Squash

I grew up in a place where the majority of people look somewhat like me. As a whole, people from Hawaii could be categorized as brownish, Asian-ish, Polynesian-ish, White-ish. While I might be an oddity in most of Latin America, when I’m back home on Hawaii Island (AKA the Big Island), I could easily pass for anybody’s cousin. There’s a saying in Hawaii, “Chinese, Japanese, olo olo, squash,” meaning that, as a population, we’re a big racial mix.

There’s a common narrative that the US is a “melting pot” of race and culture. But in college, I took a sociology class on race and ethnicity, wherein my professor pointed out that the US is more like a stew. There are a lot of different things in there, but they’re mostly distinct chunks that don’t integrate. In Hawaii, the melting and melding is more pronounced. On the Big Island, in the 2020 census, nearly 30% of residents identified as two or more races. As of 2020, 56% of the population of the state is “Asian alone or in combination.” In fact, so many of us are a mix of Asian and European descent that we have a specific and very common Hawaiian word for it: hapa.

Not That Kind of Asian

When I went away to attend the University of Virginia at 18, I had my first experience of being a racial and ethnic minority. And visually, I guess it wasn’t all that dramatic. Most of the students at U.Va. come from within the state of Virginia, but in the Northern Virginia suburbs of Washington, D.C., there’s a huge Asian immigrant population. So, I went to school with a lot of first- and second-generation Vietnamese and Korean kids. At the time, U.Va. was about 20% Asian.

Despite looking a bit like 20% of my classmates, I found that we didn’t have much in common. The cultural differences between a first-generation Korean immigrant who grew up in the D.C. suburbs and a fourth-generation Japanese-American from the Big Island of Hawaii are vast—like an-ocean-and-a-continent-apart vast. Honestly, in retrospect, living in Virginia was like moving to another country. Not least because I felt alienated even from the people with whom I thought I might share some cultural common ground.

The Paradox of Liberal Homogeneity

After graduating, I spent five months living in the Washington, D.C., suburbs and commuting into the city. I quickly found that that culture suited me even less than that of central Virginia. So in late 2013, I moved west to Colorado. I chose Colorado because I knew it would be a better cultural fit. Boulder, where I first landed, is hailed (and reviled) as a kind of privileged liberal bastion. People jokingly call it the People’s Republic of Boulder. It seems like just about everybody is a rock-climber-yoga-instructor-startup-founder, likes to hike up 14,000-foot mountains on the weekends, and starts conversations with “Epic or Ikon?” Meaning, which ski/snowboarding pass did you buy this year? People are passionate about things like recycling and composting. I’m also convinced they have one of the highest incidences of Teslas per capita in the US.

And people there care about things like racial justice—at least in theory. In 2020 the people of Boulder were out in the streets marching for Black Lives Matter, but as a whole, the residents of Boulder don’t actually hang out with many Black people. In the 2020 census, 77% of Boulder residents identified as “White alone,” and I suspect that that doesn’t include most of the seasonal population of university students, which makes up about a fourth of the city. Those students are also overwhelmingly White.

So, while I generally felt more ideologically and culturally aligned with people in Boulder, I also sometimes felt weird about the lack of racial diversity there. I remember going to a party at a friend’s apartment shortly after moving there and realizing that I was the only person of color present. It stuck with me because it was probably the first time in my life that I’d been conscious of that.

At the University of Virginia, I lived for a while with five other young women. We were a pretty diverse household. Three of those housemates are Black, one of whom is also Native American, one is White, and one is hapa—Asian and White, like me. But out of the hundreds of people I got to know in Colorado in eight years, I only had three Black friends and knew one other hapa woman. It always seemed like an apt anecdote. The representation of minority groups in my whole community in Boulder was equal to that of our single household in Charlottesville.

The Weight of Being Other

I rarely felt explicitly, consciously uncomfortable with being a member of a minority group in Colorado. As I mentioned, the people of Boulder are really liberal, and I never encountered overt racism there (though I know my Black friends occasionally have). But there is still something that can kind of wear on you after a while. It can be tiring to be constantly enveloped in a dominant culture that isn’t your own, even if it’s a welcoming one. It’s the small, sustained, cumulative effort of having to explain yourself to the people around you. In little ways. Which possibly, on an individual level, feel like they don’t really matter.

But I remember that I would feel suddenly conscious of that weight when it was lifted. Like when I’d go home to Hawaii. Or even when I’d visit California and suddenly be surrounded by diversity again. There’s a palpable ease that comes with being in a place where foundational things about my upbringing or behavior or experiences are generally well understood, or at least pretty commonplace, and there’s no need for me to explain them.

When I moved to Longmont, Boulder’s more working-class northeastern neighbor, there still were very few Asians, but there were lots of Mexicans. My neighborhood in Longmont is probably 30-40% Spanish-speaking. And though I didn’t grow up with much exposure to Latino culture in Hawaii, and I spoke no Spanish while I was living in Longmont, there was something relaxing about taking a step back from Boulder’s homogeneity.

Becoming a Third, Different Thing

Of course, after spending nearly my entire adult life living on the US mainland, I don’t fit quite as neatly into my home culture anymore, either. In the last two years, I’ve spent long periods at home, living with my parents on the Big Island. Being back there, I’ve found that I’ve become different from my classmates who’ve spent most of their adulthoods in our home. My values and lifestyle choices and even my speech have been influenced greatly by the Colorado culture (and the highly specific micro-culture of my martial arts school workplace) in which I lived for so long.

So, while it can still be comforting to be amongst people who look like me and know how I grew up, it’s not the perfect fit it once was. One of my U.Va. roommates (the hapa one) belonged to a student club called Third Culture Kids, which was made up of people who grew up abroad or in ethnically blended families. People who felt like they never quite fit into one culture or another, but rather, identified as a third, different thing. As time goes on, I can see myself becoming more of a “TCK.” Probably even more so after this big trip. While there may be something inherently lonely about it, I think it’s also freeing to let go of the expectation that I’ll be a perfect fit for anything except myself and my own life.

Stranger in a Strange Land

So, with this patchwork understanding of my racial and cultural identity, I set off for Latin America. In the last eight months, I’ve stayed in cosmopolitan metropolises and tiny pueblos smaller than my own hometown of 15,000 people. I’ve been in places on the so-called Gringo Trails of Latin America, where foreigners are commonplace and lots of people speak English. And I’ve visited places where I’ve noted that I was clearly the only Asian person in town. Maybe the only one the locals had seen this month, or occasionally, the first one they’d ever seen.

Sometimes I’m thankful for my darker Okinawan skin tone, which lets me blend in a little, at least from a distance or from behind. (Less so, now that I’ve buzzed my hair.) I’ve noticed that in very touristic places, visibly White people get a lot more offers for tuktuk rides and tacky souvenirs. But of course, once people hear my accent or get a good look at my face, they can tell I’m not from around here, so I’m far from immune to the tourist treatment. In some of the smaller, less touristic towns that I’ve been in recently in Colombia, I was conscious of getting stared at a lot.

Mis Bisabuelos

In more personal contexts and conversations, people tend to just be curious. There isn’t a huge contingent of people from Hawaii making their way to this part of the world, so for most of the people I encounter, I’m the first such person they’ve ever met. It’s not uncommon for people to initially assume that I’m from China, Japan, or Thailand. Or once I tell them where I’m from, they might assume that I’m Native Hawaiian (which is something I frequently have to clear up for people in the US, also).

In Latin America, particularly outside of touristic areas or bigger cities, I’ve acutely experienced the familiar phenomenon of having to explain myself. And it’s a lot more explicit here, which is understandable because I’m a lot more unusual here. There’s a lot of, “Who are you? Where are you from? What are you doing here?” If I only tell people I’m from the US or Hawaii, there’s usually a follow-up of “…but your face looks…” somewhat regularly accompanied by them pulling the skin around their eyes back to demonstrate to me how I look to them. When I tell them my bisabuelos, or great-grandparents, were from Japan, there’s always some variation of “Aha! See? I knew it! That’s why your face is like that!”

Looking at Context

I won’t lie. Even though I know people mean well, I’m a little tired of that conversation. And it’s a little uncomfortable to constantly have people constantly doing the Asian eye imitation thing. I come from a country where that is distinctly not kosher. I’ve spent a lot of time thinking about it, and I had a bit of a hard time analyzing exactly what it is that makes me uncomfortable. It’s not that it’s inherently rude or racist. I do think that intentions matter, and context does, too.

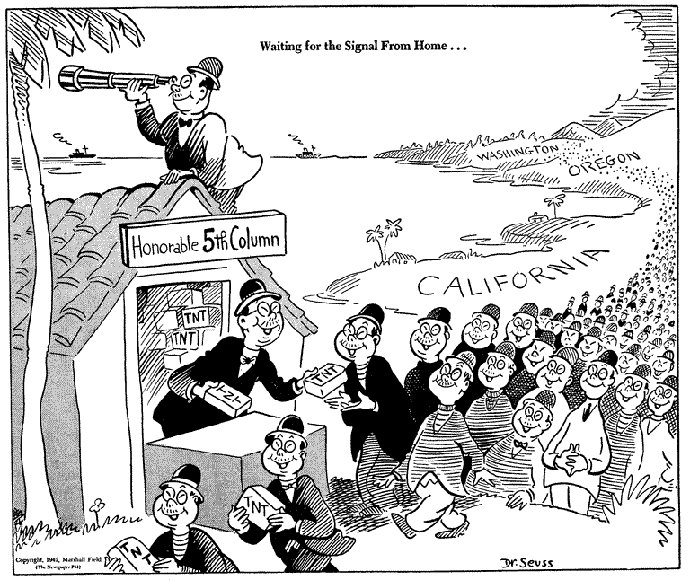

For example, in Hawaii, when kids do the “Chinese, Japanese, olo olo squash” thing that I mentioned earlier, it’s usually accompanied by pulling and then smooshing the skin around the eyes. But maybe it’s different because we are Chinese, Japanese, olo olo squash. When somebody outside of that identity does it, particularly in the broader context of the history of anti-Asian racism in the US, it can feel pretty loaded. I’m the great-granddaughter of an innocent man who spent WWII imprisoned in various US concentration camps while his sons served in the US military and his wife died back home in Hawaii. One of those camps was in Colorado, and I visited the site with my dad when he came to see me in Colorado a few years ago. It’s a pretty grim chapter of US history, and it wasn’t that long ago.

There are a lot of people in the US who have used this same eye-pulling gesture with the intent to mock and malign people of Asian ancestry. Certainly during WWII, but it’s not something that has gone away. In fact, I think the reason it feels uncomfortable to me is that nobody in the US would make that gesture with kind intentions. Racism and hate towards Asian people in the US is far from being a thing of the past. I was lucky to grow up in a place where I didn’t stand out because of the way I look. So I was never a victim of anti-Asian bullying as a kid, and nobody has ever mocked me for my Asian features. But I still belong to the broader US culture, and I’m aware that it happens and it can be really harmful. So when I see people who come from a different cultural context gesturing in a way that–at least to me–feels so loaded, it can be jarring.

Is This My Responsibility?

In places where there simply haven’t been enough Asians to attract generalized hate or discrimination, I get that people have totally innocuous intentions when they pull their eyelids back. But it still feels pretty cringe. Nonetheless, as I’m writing this, I’ve realized that I’ve literally never told someone that it’s not cool to do. Maybe because it often happens with people I’ve just met, and I normally don’t feel like getting in a prolonged discussion, educating a Colombian about the history of racism in the US. But I realize I’ve also let it slide with people who I do know better, in contexts where I could’ve made it an educational experience without inviting conflict.

Is it my responsibility? Maybe. As the only Asian person from Hawaii these people have ever met, maybe I’ve chosen the ambassador/educator role simply by choosing to be here. As a person who hasn’t personally experienced racial trauma, but understands its impacts, maybe I have the responsibility to be patient where others would be more triggered. Maybe I can and should use this knowledge and empathy to prevent future conflict.

If I’m being really honest, I can’t say that that idea is super appealing to me. For now, I think if I have another opportunity to explain this to someone with whom I have some rapport and trust, I’m willing to put in that work. But otherwise, I need to remind myself that if I’m not willing to educate, I can’t expect that anyone else has been. And at least in this part of the world, I can’t be mad at someone for not knowing something they’ve never been given an opportunity to learn.

I read this. I have nothing relevant to say.

Its a dark chapter and we’ve never faced it. Kina like slavery.

Yeah I think that probably one of the biggest roots of racism and discrimination in the US today is the cultural obsession with looking the other way… as a society we’d rather pretend it’s not happening than do the difficult work of acknowledgment and repair.

I can’t say that I didn’t shed some tears reading this Sachi. I felt some relief for your putting into words so succinctly similar feelings I’ve had in different social settings even in Hawaii or living in different states on the US mainland. Although my experiences may have been different from yours, they do share a common thread. Thank you for “lifting the lid” off my pot and I’m sure for many others.

Thanks for reading, Mom 💕

I’m glad you liked it and found it relatable