I must not fear. Fear is the mind-killer. Fear is the little-death that brings total obliteration. I will face my fear. I will permit it to pass over me and through me. And when it has gone past, I will turn the inner eye to see its path. Where the fear has gone there will be nothing. Only I will remain.

Bene Gesserit Litany Against Fear

Frank Herbert, Dune

You have the gift of a brilliant internal guardian that stands ready to warn you of hazards and guide you through risky situations.

Gavin de Becker, The Gift of Fear

You’re So Brave

“You’re so brave,” is something I’ve heard a lot from friends and family back home in the US, talking about my decision to embark on a long-term solo trip. It feels a little weird to be called that. I think I associate bravery with a certain measure of recklessness. I’m actually a very cautious person—maybe even over-cautious. What can I say? I’m risk-averse. I always wear my seat belt, snowboard and bike with a helmet, and will only jump off a cliff into a body of water if I see someone else do it successfully first.

Fear Without Danger

But maybe bravery and caution aren’t mutually exclusive. I think there’s a lot of value in differentiating between the things that feel scary because they are dangerous, and the things that feel scary because I have some kind of mental block associated with them. The former case calls for an abundance of caution and trusting of instincts. But I’m starting to think of the latter as a summons.

For example, in 2021 I started taking voice lessons with my friend and Muay Thai training partner, Morgan. I wanted to do it because 1) I think I’m happiest when I’m learning something in a concentrated, somewhat formal way, 2) I like to sing, but 3) I’ve always been pretty self-conscious about it. Singing is scary, but not dangerous.

Sometimes going toward the thing that scares you is the best way forward. And maybe that’s bravery. I recently met a guy in Medellín, Colombia, who told me that as a kid, whenever he was afraid of something, his hard-ass military dad would shove him (supervised) into that scary situation to show him it was okay. Like making him hold a snake as soon as he began to develop a phobia. Now that he’s an adult, he says he appreciates the intent and the lessons, but would probably handle it differently with his own kids. I agree, it’s a pretty harsh parenting technique, and depending on the kid, you might give them some lasting trauma. But when you can make that choice for yourself (as an adult or child), and face the thing you’re afraid of with intention, you’re going to come out better.

Working at a Jiu Jitsu and Muay Thai school for most of my adult life, I became a firm believer that we can find growth in discomfort. Pushing yourself to do something you didn’t think you could do is powerful. If you’d told me when I was 21 that at 28 I’d fight in a Muay Thai smoker in front of a couple hundred people, I’d have said, “What’s Muay Thai?” but also, “No way. That’s terrifying,” but also, “Badass!”

Was it dangerous? Not really. Nobody is getting knocked out at the Easton In-House Smoker. But for me, like every other step of advancement in Muay Thai, it was a really intimidating thing to take on. But I did it. I chose something because I knew it would be difficult, and I had fun, and I’m proud of that.

“Dangerous Places”

I think part of the reason people have been telling me I’m brave is because of their perceptions of this part of the world. I’m in Latin America. Aren’t the countries I’m visiting dangerous? Full of violence and crime? What about the drug cartels? I wasn’t immune to this. I definitely had some safety concerns when I first started researching and planning. And sure, there are some scary things happening. Some of the countries I’ve visited continue to struggle with gang- and drug-related violence in certain regions. But I’m not likely to be a victim of this kind of violence just by being within their borders. Most areas that are popular with tourists are pretty safe.

And though back home we are pretty quick to make sweeping generalizations about safety in the developing world, the US feels pretty dangerous right now, too. In recent years, the places I’ve called home on the US mainland have experienced a white supremacist rally and a mass shooting (Charlottesville) and a wildfire that burned 1000 buildings and another mass shooting (Boulder). And these are generally considered very “safe” cities.

I don’t say this to suggest that people should be living in fear at home, too. Just that we take a closer look at the xenophobia and fear-mongering that make for good headlines but prejudicial mindsets. I think that with some research and reasonable precautions, there are safe ways to visit most parts of the world.

No Dar Papaya

Petty crime is a more pressing concern. Though a high rate of theft doesn’t necessarily mean that a place is unsafe, it is a related metric. It goes hand-in-hand with a certain level of poverty and desperation to survive. There’s a Colombian idiom, “No dar papaya,” which literally means, “Don’t give papaya,” but figuratively means, “Keep your guard up. Don’t be an easy target.” In the bigger cities of Colombia there are areas where you shouldn’t flash an iPhone or a Rolex, and everybody’s wearing their backpack on their chest. You need to assume that if you give an opening, someone will take advantage.

For me, this is a weird thing to get used to. In all of the places I’ve lived, I’ve never given too much thought to the possibility of being a victim of theft. Which isn’t to say it hasn’t happened–and I guess that makes sense. In my small hometown of Waimea 13 years ago, someone broke my car window late at night while I was sitting within view of it down the street. In Boulder I forgot to lock my car door in my driveway one night, and someone stole some stuff out of it while I slept. A year later, in my very suburban neighborhood in Longmont, it happened again. So maybe I’ve just been naive, and you should always be protecting yourself from other people.

Part of me resents having to do so, but I’m learning. Recently in Colombia, someone stole my leggings off a clothesline where I figured I could leave them to dry. One day in Puerto Rico, I realized that someone had stolen a bunch of cash out of my wallet. I had left it unattended in a place where I was pretty sure it would be safe. I’m no longer making that kind of assumption. I lock up my valuables even when it seems like the people around me are trustworthy. I cover the back of my phone when I use it in public so people can’t see that it’s an iPhone (they cost a lot more in Latin America than in the US). I try not to take it out at all in places that feel too busy. I wear my fanny pack like a sling, and my thrift store wallet is leashed to a ring I sewed into the lining. I don’t leave my things unattended in the open.

Though I was bummed to lose my favorite leggings, and I could’ve bought new ones with the cash I lost, nobody has stolen anything super important from me (yet, knock on wood). And even if someone takes my phone or my passport or my credit card, they’re just things, it’s just money, just logistics. I’m not handing out any papayas, but I’m also not living in constant fear of thieves.

Functional Fear

However, there are things that are truly dangerous, and fears that are legitimate, useful, and worthy of our full attention. In The Gift of Fear, Gavin de Becker talks about the uncanny power of intuition, and how listening to your gut feelings can save your life. De Becker encourages readers to throw out our societal conditioning to be “nice” in uncomfortable situations, and focus on self preservation first. If you feel uneasy around someone, you need to believe yourself and get out of there.

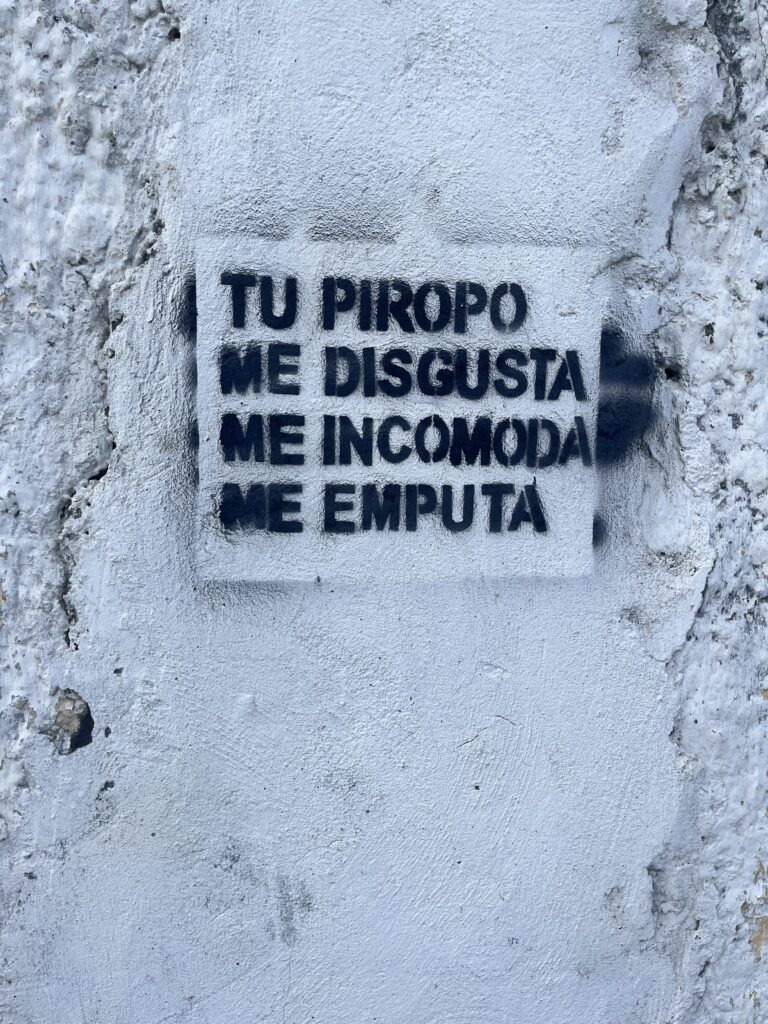

As a woman traveling alone, there’s one threat that looms larger and more immediate than anything else, and it’s one that will be with me everywhere I go in the world and in my life—men. Violence against women, sexual or otherwise, is way more prevalent globally than violence related to drugs or political unrest. It’s something that happens even in the “safety” of wealthy nations, small towns, and close families. And there aren’t a whole lot of women doling out this violence. And though I could absolutely get raped and murdered in the US, I’m more conscious of my vulnerability out here, far from my support system, in unfamiliar territory.

This is just the stark reality of being a woman. It sucks, and it’s not fair, but it’s real, and it’s not going away just because we hate it. I’ve had a few conversations with male friends about times where they’ve felt afraid, vulnerable, or threatened, and suddenly realized for the first time that that’s how most women feel on a pretty regular basis. There are considerations that I have to take that a man in the same position often wouldn’t. I have to be careful about the amount of trust and power I give to strangers. I always have to be on the lookout for people who might mean me harm. I can’t take simple questions at face value—a man could be making conversation, just being friendly, or he might be scouting for an opportunity to do me harm. When asked if I’m traveling alone, I usually lie.

I was recently in Cartagena, Colombia, which is one of the most popular tourist destinations in the country. But it was also the place where I felt most unsafe. I had a couple of pretty unpleasant interactions with men, where I was very aware of my vulnerability and their untrustworthiness. To my knowledge, I didn’t have any truly close calls–I don’t think I was in serious danger in those moments. But it was enough to put me on edge. Even though I would’ve liked to go check out the night life and the Christmas lights in the historic city center, I opted to stay in after dark. I think that whole experience would’ve felt different if I’d been traveling with a man.

That said, I did befriend some decidedly kind, trustworthy, and well-intentioned men in Cartagena. I count that as a win, because I feel like it’s proof that my radar is working. I can trust myself to pick up on someone’s energy pretty quickly. Obviously it still pays to take precautions, but I’m gaining a better understanding of which fears come from credible threats.

I’ll Choose Brave

So, is it scary traveling alone? Honestly, at this point, I’m more scared not to. When people ask what I’m afraid of, it’s not the dark or spiders or heights (though please don’t sign me up for bungee jumping). I’m scared of feeling like I didn’t spend my lifetime well. I don’t want to wake up at 40–or 80–and realize that I never did the things that matter to me. One of the most common things that dying people regret is not having had the courage to live a life that was true to themselves. I aspire to live a life that’s overflowing with that kind of trueness. I’m working every day to find alignment.

In six months of travel in Latin America, most of the people and places I’ve encountered have felt safe. So many people have helped me, given me good advice, and been nothing but kind. I’ve learned more about trusting myself and listening to myself and paying attention to the people, places, and situations that feel right for me. I’m choosing. I’m careful, but I’m not hiding from the world. And if that’s what people want to call bravery, I’ll take it.

YOU GO GIRL!

Thanks Mom 🙂

So beautiful!! I’m getting ready to solo travel in South America soon, and you managed to sum up so many thoughts and feelings I didn’t even know I had 🙂

Aw thanks, Jess! Stoked it resonated.